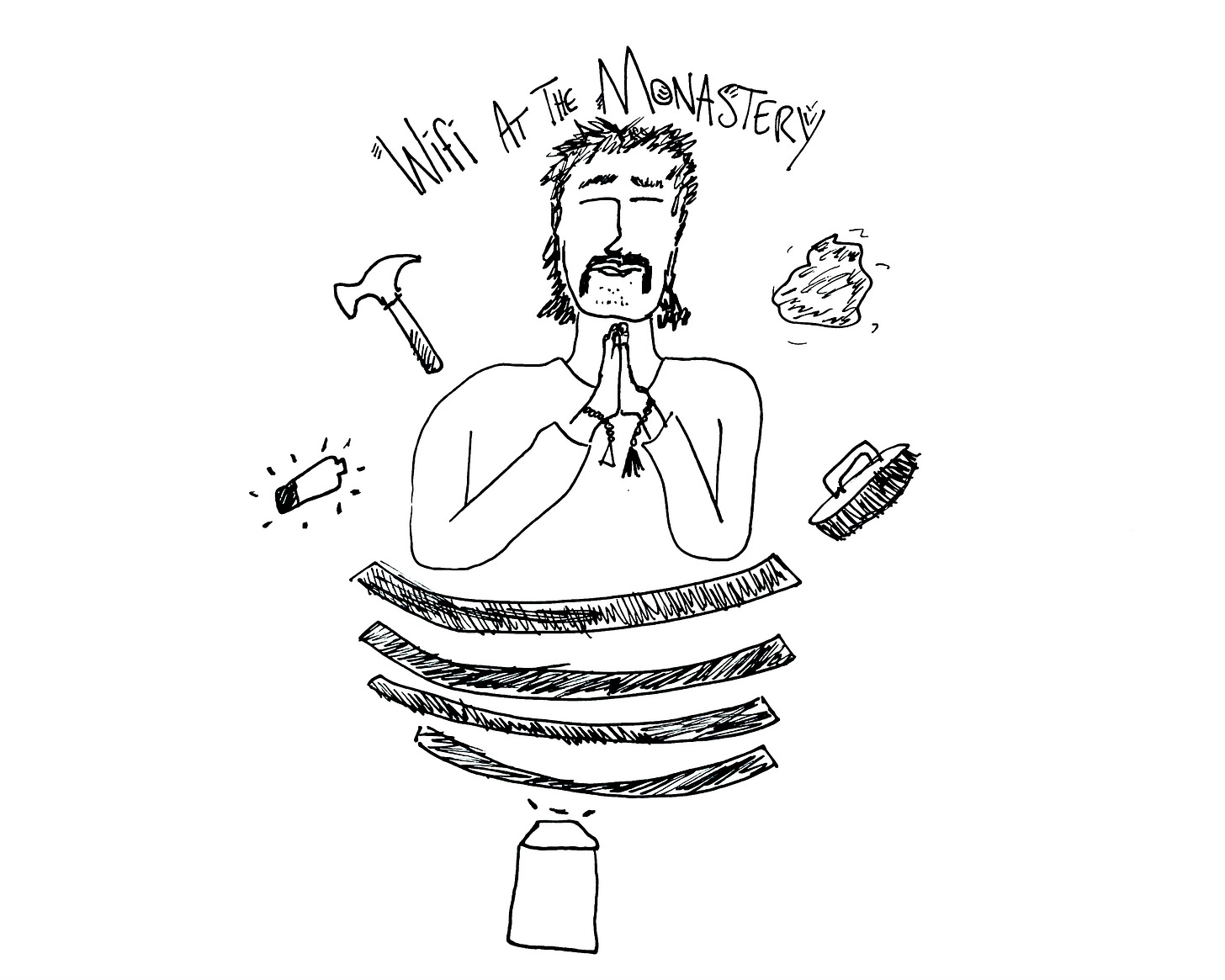

For the first year at the monastery, I wasn’t allowed to ask questions. It was mostly scrubbing floors, peeling potatoes, and light roofing repair.

There was always a draft, always a small, incessant leak somewhere in the building as if the monks had taken an oath of water torture in tandem with austerity. They claimed they had also taken vows of passivity, which prohibited them from swinging a hammer.

The uninitiated, however, were conveniently allowed to labor. Every day, I received my punch list.

- shovel the walkway

- water the plants

- patch the drywall

- build their IKEA furniture

Did they want more gravel on the walkway, or did they need it cleared? What plants needed watering? Do we keep drywall mud on hand? Which one of you sons of bitches is lying about punching holes in the wall? And who schlepped this chic Swedish dresser up the side of the mountain?

These and all other questions were verboten until I’d proved myself worthy of answers. Until then, any slight rise in vocal inflection was met with the assignment of longer, more laborious chores. They got sick of my inquisitive expressions and shrugged shoulders, too. I’m pretty sure they started salting my water.

I forged ahead without knowing where the shovel was or who kept shoving their fists through plaster; I always assumed they were happy with my work because I couldn’t inquire about their satisfaction. The first few months went on like that.

It started to feel like I wasn’t even on the path to enlightenment, that I got suckered into working as the super for some backwoods cloister where the compensation was light physical abuse and the occasional hot meal. It got me wondering why I’d even joined in the first place.

One of the lower ebbs of my life, I had taken a sales job with Radon Internet, where I was to canvas the lower 48 systematically from top right to bottom left — it was owned by some Taiwanese conglomerate. My supervisor was a man named Pai-Han, which I thought was ‘Pie Hand’ for my entire training period, and he shuddered every time I said Taiwan, not Taipei, and was convinced Edward Hopper-style diners were on every American street corner. Alright, Pie Hand.

It wasn’t long before I hit the Northern Appalachians after they set me out on my own. The newly formed American arm of the company got its name due to a low-effort translation error. The parent company was called Ruì-Dōng Internet, which means roughly Lucky East. The higher-ups on the board were Chinese loyalists who refused to devote serious time to their American English lessons and were quite pleased when the pronunciation of the brand name in their mother tongue sounded a little like Ray Dawn. Kismet.

They shortened it to one word due to the perception that Americans were reluctant to read two, hired a sales team, and marooned me on a Maine beach with a few pamphlets and a cell phone.

So, there I was, in a wilderness, outnumbered 5:1 by deer, black bears, and expat Canucks fleeing the Trudeau regime, hocking an upstart internet service that shared its name with a harmful chemical you treat your home against. Things were really looking up.

To a better next week,

~FDA

😂 Hahaha